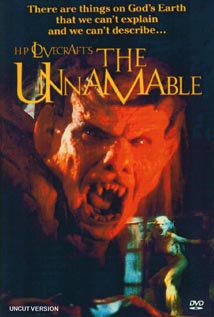

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Unnamable,” written in September 1923 and first published in the July 1925 issue of Weird Tales. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

“Moreover, so far as aesthetic theory was involved, if the psychic emanations of human creatures be grotesque distortions, what coherent representation could express or portray so gibbous and infamous a nebulosity as the spectre of a malign, chaotic perversion, itself a morbid blasphemy against Nature? Moulded by the dead brain of a hybrid nightmare, would not such a vaporous terror constitute in all loathsome truth the exquisitely, the shriekingly unnamable?”

Summary: Carter and his friend Joel Manton sit on a 17th century tomb in Arkham’s old burying-ground. An immense willow inspires Carter to speculate on the “unmentionable” nourishment it must suck from the charnel ground. Manton scoffs that Carter’s use of words like “unmentionable” and “unnamable” is a puerile device, just what you’d expect from a hack writer. No doubt he says this with love, but Carter’s inspired by their eerie setting to defend his dark romanticism from Manton’s rationalistic world view. (It’s also rich of Manton, conventionally religious and selectively superstitious, to lecture Carter on objectivity.)

Carter knows Manton half-believes in astral projection and in windows that retain the images of those who peered through them in life. If Manton credits these things, he admits to the existence of “spectral substances… apart from and subsequent to their material counterparts.” Simply put, he believes in ghosts. Is it then so hard for him to believe that spirit freed from the laws of matter might manifest itself in shapes—or lack of shape—that the living couldn’t name or adequately describe?

As dusk falls, the two argue on. Carter supposes his friend doesn’t mind the wide rift in the brickwork of their tomb, or that the deserted house tottering over them cuts off illumination from the streetlamps. He tells Manton what inspired his story, “The Attic Window,” another target of Manton’s derision. In Magnalia Christi Americana, Cotton Mather wrote of a monstrous birth, but it took a “sensationalist” like Carter to imagine the monster growing up. To Mather’s laconic account, Carter added ancestral diary entries and records of a boy who in 1793 entered a deserted house and emerged insane.

In the dark Puritan days, a beast (maybe a cow? a goat?) gave birth to something “more than beast but less than man.” The hybrid creature had a blemished eye, like that of a town wastrel later hanged for bestiality. People whispered about a broken old man (the wastrel’s father?) who locked his attic door and put up a blank grave marker (for the hanged drunkard?) Locked door or not, something with a blemished eye began to peek into windows at night and wander deserted meadows. Carter’s own ancestor was attacked on a dark road and left scarred as if by horns and ape-like claws. Inhabitants at a parsonage didn’t get off so easy—whatever descended on them left none alive or intact. Such incidents continued after the old man’s burial behind his house, but eventually the monster took on a spectral character. If it was ever truly alive, people now supposed it dead.

Manton is impressed. Nevertheless he insists that the most morbid perversion of Nature must be describable, namable. Carter contends that if the psychic emanations of normal humans are grotesque apparitions, what must the emanation, the ghost, of a monster be? Shriekingly unnamable, man.

Manton asks if Carter’s seen the deserted house. Carter says he’s been there. The attic windows were now glassless. Maybe the boy in 1793 broke it all from fear of what he saw in it. But Carter did find a skeleton, with an anthropoid skull bearing horns four inches long. He brought the bones to the tomb behind the house and threw them in through a rift in its brickwork.

When Manton wishes he could see the house himself, Carter says he did see it, before it got dark. In other words, it’s the deserted hulk beside them, and they sit on the tomb where Carter deposited the terrible skeleton.

Manton’s reaction startles Carter, the more so when his friend’s cry is answered by a creak from the attic window above and a burst of frigid air. Something knocks Carter to the ground, while from the tomb comes such a whirring and gasping that it might contain whole legions of misshapen damned. More icy wind, and the sound of bricks and plaster yielding, and Carter faints.

He and Manton wake the next day in St. Mary’s Hospital. Carter bears the mark of a split-hoof, Manton two wounds like the product of horns. They were found far from the cemetery, in the field where a slaughterhouse once stood. Manton remembers enough to whisper the terrible truth to Carter. He told the doctors a bull attacked them, but their real assailant was “a gelatin—a slime—yet it had shapes, a thousand shapes of horror beyond all memory. There were eyes—and a blemish. It was the pit—the maelstrom—the ultimate abomination. Carter, it was the unnamable!”

What’s Cyclopean: A ghastly festering bubbles up putrescently.

The Degenerate Dutch: This time, Lovecraft sticks to being rude about Puritans. And anti-genre literary snobs.

Mythos Making: A lot of people identify this story’s Carter with our boy Randolph, though the characterization doesn’t quite add up—the guy who made the Statement should be a little more cautious about calling up that which he’s sitting on. This story’s Carter either doesn’t believe his own arguments, or takes a Hound-ish glee in the danger he’s setting up. The latter is plausible, given his schadenfreude when his wounded companion’s at a loss to describe their assailant. What a jerk.

Libronomicon: You really need to be careful about reading old family diaries. Small mercies: the risk isn’t as great for a Carter as for a Ward.

Madness Takes Its Toll: When the boy in 1793 looks through the windows of the old house, what he sees there drives him mad.

Anne’s Commentary

By lucky coincidence, our last story (“The Hound”) ends with the word “unnamable,” this one’s title and subject. Another similarity: Lovecraft again “casts” a friend as a character, here Maurice Moe, who like “Joel Manton” was a high school teacher and religious believer. Moe fares better than Kleiner (Hound’s “St. John”)—he gets moderately gored, not ripped to shreds. “Carter” is probably Lovecraft’s alter-ego, Randolph Carter; “The Silver Key” (1926) notes that Randolph had a harrowing adventure in Arkham (among willows and gambrel roofs) that caused him to “seal forever” some pages from an ancestor’s diary.

Two-thirds of the text condenses the argument between Carter and Manton—only halfway down the penultimate page do we get dialogue and brief action. The dispute reads like a defense of Lovecraft’s literary credo. One can imagine he was driven to write “The Unnamable” in response to actual criticism. Broadly viewed, he pits a romantic-fabulist against a rational-naturalist. Nothing can be unnamable—that doesn’t make sense! No, failure to appreciate the concept of unnamability shows a dire lack of imagination! No, because if something can be perceived via the senses, it must be describable! No, there are things beyond the material, hence beyond the apprehension of the senses!

So far, so good. But the distinctions between our combatants are in fact more complex and thought-provoking. Manton may be pragmatic and rational, but he’s also conventionally religious and credulous of certain bits of folklore. He believes more fully in the supernatural, thinks Carter, than Carter himself. A contradiction on the surface, unless one supposes that Carter has seen enough to believe nothing is beyond nature, though it may be beyond present understanding. Carter argues for nuance, for attention to “the delicate overtones of life,” for the imagination and the metaphysical. But he appears to be a religious skeptic, and it’s he who tries to buttress his ideas with research and investigation. Manton listens to old wives’ tales. Carter delves into historical documents and visits the sites of supposed horror.

Carter’s attitude toward one of his sources—Cotton Mather—is especially interesting. He has little sympathy for the great Puritan divine, calling him gullible and flighty. The Puritan age itself is “dark”, with “crushed brains” that spawn such horrors as the 1692 witch panic. “There was no beauty, no freedom,” only “the poisonous sermons of the cramped divines.” The period was, overall, “a rusted iron straitjacket.” Not the attitude we might expect from Lovecraft the antiquarian, but his real love seems to be the coming century of enlightenment and Georgian architecture.

Curiouser and curiouser: If an era of repression can create monsters, so can an era of licentiousness, like the decadent close of the 19th century that produced the ghouls of “The Hound.” Balance, a keystone of the (Neo)classical era, may encourage a sturdy morality, though not a great literature of the weird. Lovecraft might have liked living in 18th century New England, but to make it horrible, he dragged in long-lived Puritans, that is, Joseph Curwen and friends. Pickman of “Model” fame will also harken back to the Puritans for real horror, but he also recognizes their lustiness and adventurous spirit.

Anyhow. I earned tome-reading points this week by cracking Mather’s Magnalia Christi Americana (The Glorious Works of Christ in America) and finding the passage that Lovecraft summarizes:

“At the Southward there was a Beast, which brought forth a Creature, which might pretend unto something of an Humane Shape. Now, the People minded that the Monster had a Blemish in one Eye, much like what a profligate Fellow in the Town was known to have. This Fellow was hereupon examin’d, and upon his Examination, confessed his infandous Bestialities; for which he was deservedly Executed.”

In the next book of Magnalia, I stumbled on an even juicier bit, which refers to a woman whose infection with foul heresies caused her to conceive a devilish child:

“It had no Head; the Face was below upon the Breast; the Ears were like an Apes, and grew upon the Shoulders…it had on each Foot three claws, with Talons like a Fowl…upon the Back…it had a Couple of great Holes like Mouths…it had no Forehead, but above the Eyes it had Four Horns…”

Yikes, and that’s a fraction of the anatomical detail Mather lavishes on this “false conception.” Speaking of which. In one literary mood, Lovecraft may rely heavily on fanciful figures and the “uns”—unmentionable, unnamable, unspeakable. In another, no one can beat him for minute scientific detail. Look at the descriptions of the Elder Race of Antarctica! Wilbur Whateley revealed! The Yith and their Australian stronghold!

This read I think I’ve parsed out the attack scene better. Carter wonders if the spectral phase of the attic monster is dying “for lack of being thought about.” And sure enough, it manifests at the exact moment when Manton is shocked into gulping credulity, as if the psychic energy of his belief and fear returns it to full potency. First it’s a spectral burst from the attic, then a more material horror as spirit and skeletal remains combine.

Many intriguing threads in what I once thought a slight tale. Here’s another short story with material enough for a novel. And the Being of the Blemished Eye is a fine terror, like most Beings that peep in windows at night….

Ruthanna’s Commentary

In contrast to last week’s overwrought bit of angst, I can’t help enjoying this bit of self-indulgence: a delightful violation of all laws of god and authorship. It does everything wrong, from the self-insert writer-as-protagonist to the “I’ll show you” at mainstream critics that only succeeds because the author cheats. But it’s fun.

And it gets at an interesting question: can something really be unnamable? In the flip sense, no—I could name this story’s morbid blasphemy Matilda, and have done with it. But that wouldn’t be a true name, just a label forced on something that might not have an essence to name at all.

What does it mean for something to be namable? Here, it seems tied up with describable. Can you say what it looks like, share your perceptions in a way that doesn’t reduce to gibbering incoherence? Manton suggests that everything in the universe should be subject to either science or religion—analysis or moral intuition. For Manton, those are tools of authority. Someone, priest or researcher, is in charge of understanding the thing, and ought to be able to explain it even if you-the-observer aren’t up to the task. So something unnamable isn’t just hard to perceive properly, but outside the boundaries that man-made institutions set on existence.

The story touches on other ways of being unnamable, too, possibly without meaning to. The unmarked grave is the first hint we see of the unnamed. Something forgotten—names, events, history—can no longer be named, even if it once could. Other stories of Lovecraft’s show that this, too, is terrifying. Entropy swallows those who once had names and lives, turning them into legend or misunderstanding or nothing at all.

And then there’s the fact that this blasphemous creature, with horns and a human jaw, was likely related to the old man who locks it in an attic, and who chases after when it gets out. If that’s his grandkid, he probably did name it, even if only in his mind. Something might still have a name even if you don’t personally know it, and that you can’t describe something doesn’t mean no one can—an empathic deficit that shows up again and again in Lovecraft’s work. And in other people, too, for as long as there have been people. Is unnamability inherent to the nameless thing, or just to the observer who can’t or won’t name it? Is it a state, or a perception?

I’m not claiming, by the way, that the beast of the blemished eye isn’t a monster. But even monsters do better when they’re treated well, and I can’t help but think of Frankenstein’s creation, driven to behave as the world expected. Puritan New England, as Lovecraft himself implies, was not a healthy place for anyone (or anything) that fell outside very narrow boundaries. And the accommodating neighbors, witnessing and gossiping but not questioning, also remind me of later Arkhamites who see Derby-as-Asenath’s plight and do nothing to help.

The cost of Puritanical boundaries is another theme that runs through the story, including the accusations Carter levels against his critic: that he places arbitrary limits on what stories are appropriate to write, limits narrower even than real experience. And this is a fair complaint even in much of genre. As Twain points out, fiction is obliged to make sense. Reality is less considerate of humanity’s limited sense-making abilities. At his best, the willingness to push these boundaries really is one of Lovecraft’s strengths. I tend to think, though, that this works better when he shows us less limited creatures as contrast—say, the Outer Ones—than when he just assures us that something indescribable happened, and we have to take on faith that we wouldn’t have been able to describe it either.

Join us next week and learn the dreadful secret of “The Outsider.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.